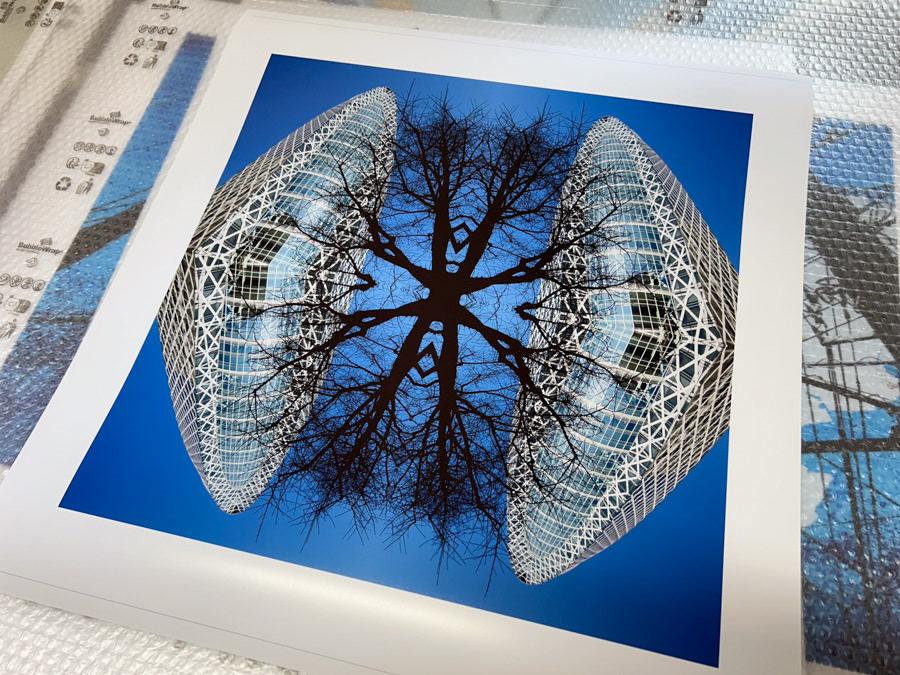

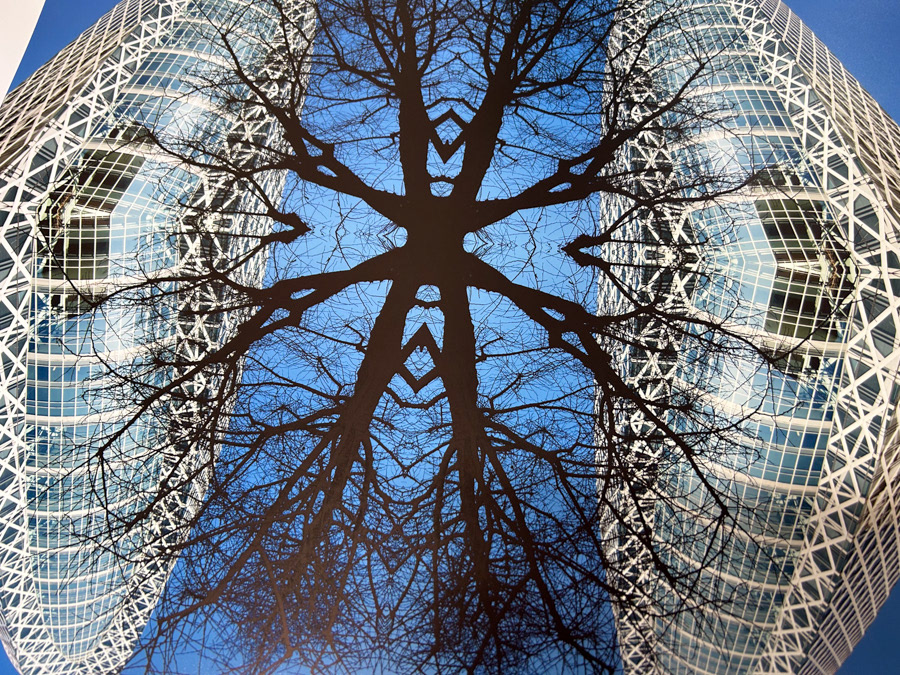

Virginio ha preso la metro per raggiungere Shinjuku, emergendo dalle viscere della terra insieme ai 3 milioni e 600 mila viaggiatori che ogni giorno ne fanno lo snodo ferroviario più trafficato del mondo. Siamo nel cuore di un’immensa conurbazione urbana, cresciuta intorno al palazzo seicentesco di un daimyō, tra venerabili ciliegi, grattacieli vertiginosi, hotel monumentali e centri commerciali smisurati.Eppure, di questa giungla metropolitana non vi è traccia nelle fotografie di Virginio che ci restituiscono un “super-mondo” altro, spogliato della sua fenomenicità ma reso leggibile nella sua struttura nervosa ed anatomica, che seduce lo sguardo, ipnotizzando la mente in geometriche visioni autogenerantesi all'infinito.Potremmo essere sul set di uno di quei film futuristici che raccontano la colonizzazione di universi paralleli da parte di intelligenze aliene o, con un po' meno fantascienza ed un po' più di scienza, scoprire che Virginio ci mostri la realtà attraverso uno di quei microchip dell'elettronica organica trasparente che individuano le reti neuronali attraverso segnali elettrici e luminosi. Ma il gioco, come il dado, è presto tratto e le sedicenti connessioni cerebrali si rivelano essere "nient'altro" che architetture riflesse tra rami spogli di ciliegi fotografati in inverno dal basso. Eppure, anche a trucco svelato, continuiamo a crederci. È come entrare nella stanza degli specchi di un Luna Park dove niente è come appare. In questo ipnotico altalenarsi di forme sospese tra sogno e realtà, in cui la coscienza interroga l’illusione e l’illusione, a sua volta, genera nuova coscienza, la fotografia diventa metamorfosi della visione ed apre coraggiosamente un varco su geometrie impossibili che sarebbero piaciute ad Escher, labirinti infiniti come quelli narrati da Borges, passando per universi mentali del Nolan di Inception, fino alle visioni riflettenti di San Paolo di Tarso.Se volessimo trovare un corrispettivo letterario, potrebbe essere l’entrelacement, l’intreccio continuo, ossessivo di immagini che si sovrappongono, si moltiplicano, scompaiono e riemergono, frantumandosi e moltiplicandosi sulle superfici specchianti di una città distopica e politopica insieme. E noi abbiamo la sensazione di essere tra quei milioni di sguardi che ogni giorno attraversano Shinjuku, isolati eppure vicini, che alla fine si fondono in un unico sguardo sinaptico che diventa lo sguardo della città stessa per poi sublimarsi in una coscienza collettiva, in costante metadialogo e metavisione con se stessa, di se stessa e per se stessa. Virginio è un regista e si vede: spalanca l’accesso al proprio immaginario, a quel suo personale “sogno condiviso”, facendoci pensare quello che lui pensa, facendoci credere quello in cui lui crede, ruotando l’obiettivo come una trottola, fino a che il suo sguardo diventa il nostro. Non c’è trucco, non c’è inganno, ma l’enigma della visione resta un enigma.

Virginio took the subway to reach Shinjuku, emerging from the bowels of the earth together with the 3.6 million commuters who make it the busiest railway hub in the world every day. We are in the heart of an immense urban conurbation, grown around the seventeenth-century palace of a daimyō, among venerable cherry trees, dizzying skyscrapers, monumental hotels, and boundless shopping centers.

Yet there is no trace of this metropolitan jungle in Virginio’s photographs, which return to us an entirely different “super-world,” stripped of its phenomenal appearance but made legible in its nervous and anatomical structure, seducing the gaze and hypnotizing the mind with geometric visions that self-generate endlessly.

We might be on the set of one of those futuristic films that depict the colonization of parallel universes by alien intelligences, or—with a little less science fiction and a little more science—discover that Virginio is showing us reality through one of those transparent organic-electronics microchips that map neural networks through electrical and luminous signals. But the trick, like the die, is soon cast, and the supposed brain connections reveal themselves to be “nothing more” than reflected architectures among the bare branches of cherry trees photographed from below in winter. And yet, even with the trick revealed, we continue to believe it. It is like stepping into the hall of mirrors at a funfair, where nothing is as it seems.

In this hypnotic oscillation of forms suspended between dream and reality, in which consciousness interrogates illusion and illusion, in turn, generates new consciousness, photography becomes a metamorphosis of vision and boldly opens a passageway onto impossible geometries that Escher would have loved—endless labyrinths like those narrated by Borges, mental universes like those of Nolan’s Inception, all the way to the reflecting visions of Saint Paul of Tarsus.

If we wished to find a literary counterpart, it might be entrelacement—the continuous, obsessive interweaving of images that overlap, multiply, disappear and reappear, shattering and multiplying across the mirror-like surfaces of a city that is both dystopian and polytopic. And we feel as though we are among those millions of gazes that cross Shinjuku every day, isolated yet close, ultimately merging into a single synaptic gaze that becomes the gaze of the city itself, only to sublimate into a collective consciousness in constant metadialogue and metavision with itself, of itself, and for itself.

Virginio is a director, and it shows: he flings open the gates to his own imagination, to his personal “shared dream,” making us think what he thinks, making us believe what he believes, spinning the lens like a top until his gaze becomes our own. There is no trick, there is no deception, yet the enigma of vision remains an enigma.